ENERGIZED: Investment Insights on Energy Transformation

Edition 18

May the wind be at your back: why wind investment is bouncing back

19 February 2026

Please note: This newsletter is for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial, legal or tax advice nor as an invitation or inducement to engage in any specific investment activity, nor to address the specific personal requirements of any readers.

Disclosure: Ørsted was added to the Energized Portfolio in January 2026.

Key Takeaways:

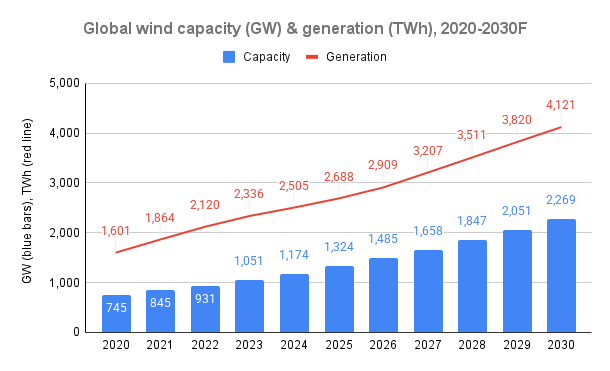

Global wind installations hit a record 150 GW in 2025, while wind generation was on track for ~2,700 TWh/pa, up ~70% since 2020

A single new 15 MW offshore turbine can today produce over 60 GWh/pa, or 6-9x the entire output of a first-generation North Sea wind farm commissioned in 2000

But the industry has experienced its own “Gartner hype cycle”: a “peak of inflated expectations” in 2020-21 fell into the 2021-24 “trough of disillusionment”

The “slope of enlightenment” started in 2025 as developers and manufacturers navigate inflation, supply chain, market and regulatory risks to pursue more financially disciplined growth

This will lead to a “plateau of productivity” supported by electricity demand growth and project hybridisation with batteries:

By 2030, global wind capacity and generation will both rise by ~50% to reach 2 TW and 4,000 TWh/pa

By 2040, we expect wind to overtake gas as the world’s 2nd largest power source, after solar - even assuming much slower capacity growth rates

Three key dynamics drive this steady global expansion:

Chinese scale-up: ~120 GW/pa installed in 2025 reflects a step up in its wind expansion - a key pillar of energy and industrial strategy

European strategic autonomy: targeting 15 GW/pa across the North Sea region to underpin energy security and industrial competitiveness

Emerging markets adoption: rapid installation growth rates across developing countries as they pursue electrification and indigenise supply

Strong rebounds in major listed wind valuations have largely priced in this growth, but Europe’s long-term offshore buildout may support further recovery for Ørsted

More diversified wind exposure is available via wind-focused ETFs (WTFs?!), including First Trust Global Wind Energy (FAN), Invesco Wind Energy UCITS (WNDI) and Global X Wind Energy UCITS (WNDG), albeit these have all already recovered significantly over the past year.

Wind’s industry cycle has turned

“Too expensive! Too unreliable! Too ugly!”

Is there any more hated industry than wind? There’s seemingly no shortage of critics happy to write it off as a financially ruinous folly.

There’s no denying it’s faced some serious challenges. Supply chain friction, cost inflation, staff layoffs, failed bid auctions, project delays and cancellations have made it an investment minefield since 2021. Then throw in recent downturns in wind speeds in key markets and across the Atlantic, the cherry on top: the one-man ideological crusade against “money-losing windmills”.

Can such a troubled industry really play a big role in our energy future? Actually, yes. Negative headlines obscure enormous progress. Take the Oweninny expansion in County Mayo, on Ireland’s west coast, which is replacing the Bellacorick project built in 1992. Each of its 6.5 MW new turbines has more capacity than the old wind farm’s entire 21 turbines.

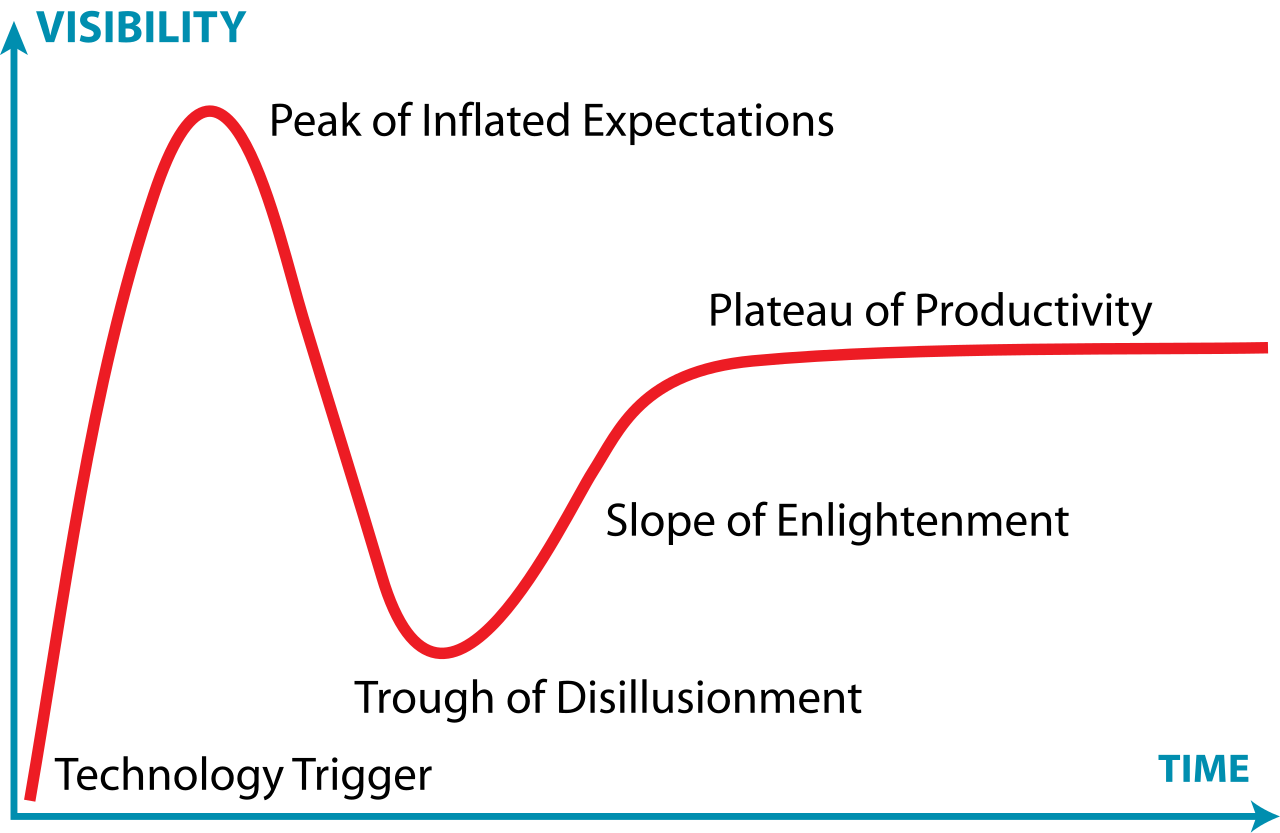

This industry is now physically unrecognisable from previous decades. But it has also been experiencing its own version of the “Gartner hype cycle” - a commonly perceived pattern for technology-based industries:

The classic Gartner Hype Cycle

Stage 1: “Technology Trigger” (2000-15)

As technology advanced and turbines grew in capacity and efficiency, the industry gradually expanded. Policy support in key markets helped drive scale and momentum while unit costs declined, leading to steady expansion.

Stage 2: “Peak of Inflated Expectations” (2015-21)

This has been covered in much greater detail elsewhere, but essentially, low interest rates, government-backed clean energy mandates and a rising sustainability agenda accelerated capital deployment and competition for assets even where returns remained limited. Expectations eventually accelerated ahead of reality, peaking in 2020-21.

Stage 3: “Trough of Disillusionment” (2021-24)

Then reality hit back. The pandemic, Ukraine war and energy crisis brought rising inflation and interest rates accompanied by supply chain pressures, exposing wind’s capex-heavy financial profile. The drive for scale ran into operational obstacles. Developers struggled to afford the high up-front seabed concession payments charged by governments.

These factors caused project delays and cancellations, hit industry economics and seized up supply chains. A vicious circle emerged of declining project viability reducing capital investments, pushing input and financing costs up, further harming project viability. The levelised cost of offshore wind rose by 50% in real terms from €64/MWh in 2020 to €95/MWh in 2024.

Investor sentiment swung back sharply from enthusiasm to scepticism. Project certainty now trumped growth potential. Who could actually deliver competitive and timely projects backed by secure grid connections? Rising curtailment also complicated the investment outlook. By late 2024, sentiment was at its low. Wind share prices were hit hard. From its peak in January 2021 to trough in August 2025, industry leader Ørsted fell by an ignominious 87%.

Stage 4: “Slope of enlightenment” (2025-27?)

However, the cycle eventually began to turn. Wind has emerged as critical for energy security amid the strategic imperative of electrification. It is a key element in the development of more resilient, reliable and affordable energy systems, alongside solar, storage, expanded grids and demand flexibility.

The EU faces a glaring strategic vulnerability: it still imports around 80% of its gas consumption. Import dependency has swung from an unrepentant Russia towards an increasingly hostile US. Energy security has become an urgent priority in a world of unpredictable enemies and unreliable friends. Maximising local energy production reduces reliance on fossil fuel imports.

This is especially true for large energy importers like the UK and Germany who desperately need to support local industries. Access to affordable energy is critical for industrial competitiveness. Norway has vast hydropower resources, France is the leading nuclear power, while southern European countries are much better placed for solar. North Sea nations must evolve from tapping the resources buried underneath the sea to the less energy dense but more accessible resources flowing above it.

This is why in January nine northern European governments made a big statement of intent: the Joint Offshore Wind Investment Pact, or Hamburg Declaration. Their shared ambition is to enable a co-ordinated European offshore wind buildout of 15 GW/pa, ultimately reaching 300 GW across the region by 2050 - 10x the North Sea’s current 30 GW capacity. Hence the Hamburg vision to go big on wind and “transform the North Sea into the largest clean energy hub in the world.”

To succeed, this strategy must provide developers, supply chains, investors and financiers with clear and predictable investment frameworks. That includes:

Speeding up planning and permitting decisions

Leveraging multilateral capital to stimulate private investment

Establishing national and cross-border Contracts for Difference (CfDs)*

Facilitating the growth of trans-national power purchase agreements (PPAs)**

The growth of the UK wind sector shows how essential CfDs are for consistent investment. CfD-backed projects are typically 2% cheaper to finance than than merchant projects. That makes them much more bankable (70-80% debt-financed vs only 30-40%).

A big increase in European offshore installations is already planned over the next decade. But Hamburg will further accelerate the North Sea’s evolution from a basin full of oil rigs and gas platforms to one dominated by gigascale wind farms. These will be increasingly integrated into a system of high-voltage interconnectors and hybrid offshore facilities designed to maximise utilisation. An example is the proposed HansaLink, a 2 GW 850km interconnector between Scotland and Germany via an offshore wind farm.

Proposed offshore capacity expansion in Europe. Source: Ørsted, April 2025

This is why we’re now in the “slope of enlightenment” phase. Plus, for developers, it is no longer just all about scale. The industry has learned some painful lessons. Developers have learned to focus on value as much as volume. Building real scale requires standardisation, not fixation on ever-larger turbines. But this lays the foundation for a more financially robust industry, focused on delivering better returns.

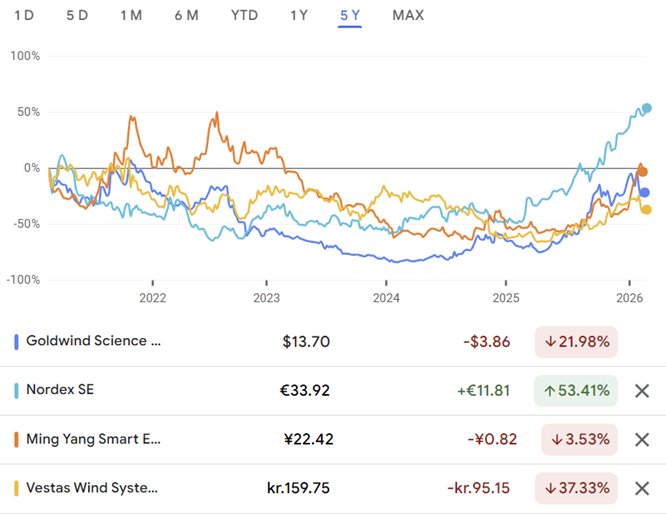

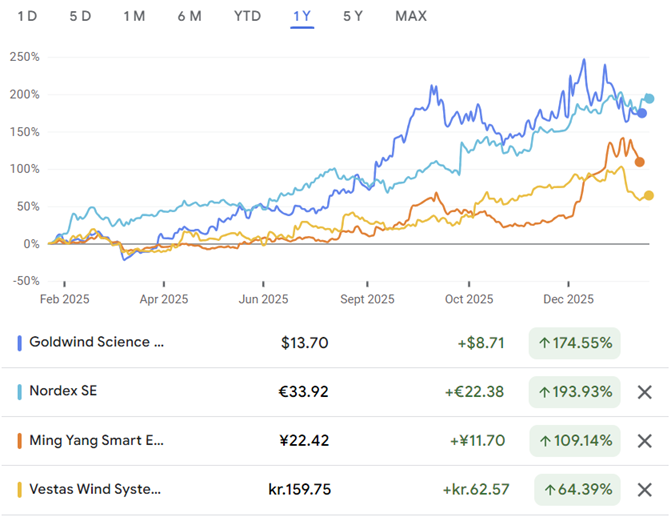

In that context, investor sentiment has already recovered sharply, sparking a remarkable turnaround for big wind manufacturers (OEMs) like Vestas, Goldwind, Ming Yang and Nordex. Some valuations have tripled - and now look stretched, even after a sharp correction over the past two weeks.

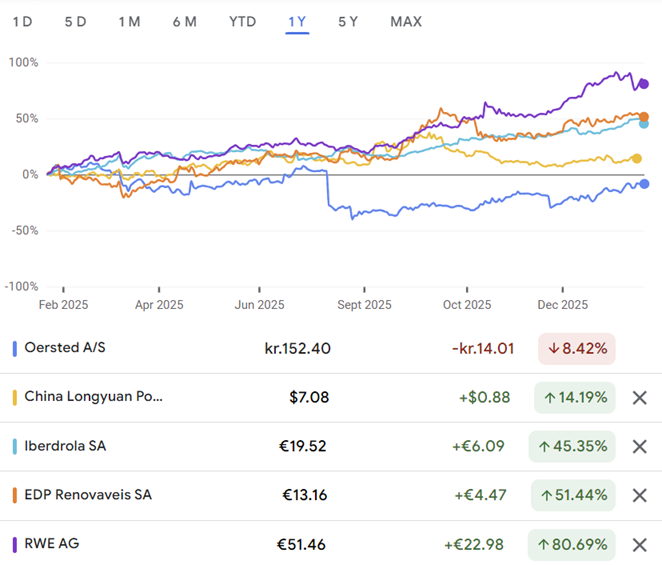

Developers are typically diversified across renewables rather than solely focused on wind. Bigger players like Iberdrola, RWE and EDPR have seen valuations grow by up to 50% over the past year, while smaller diversified players like Scatec and Acciona Energia have done even better.

Stage 5: “Plateau of productivity” (2028-beyond?)

Recent industry volatility has perhaps distracted from the consistent progress wind has made at a global level. Global capacity has grown at an average rate of 18% since 2020, albeit quite unevenly, lifting its share of electricity generation from 6% to 8.5%.

Wind’s future growth will be slower than for solar or batteries - it lacks the same degree of modular scalability, cost declines, location flexibility and installation speeds. But we will still see steady global expansion over at least the next decade, rolling out gigascale (1 GW+) projects onshore and offshore to complement other supply sources. This will be underpinned by stronger high-voltage transmission networks and fast-expanding grid-scale storage.

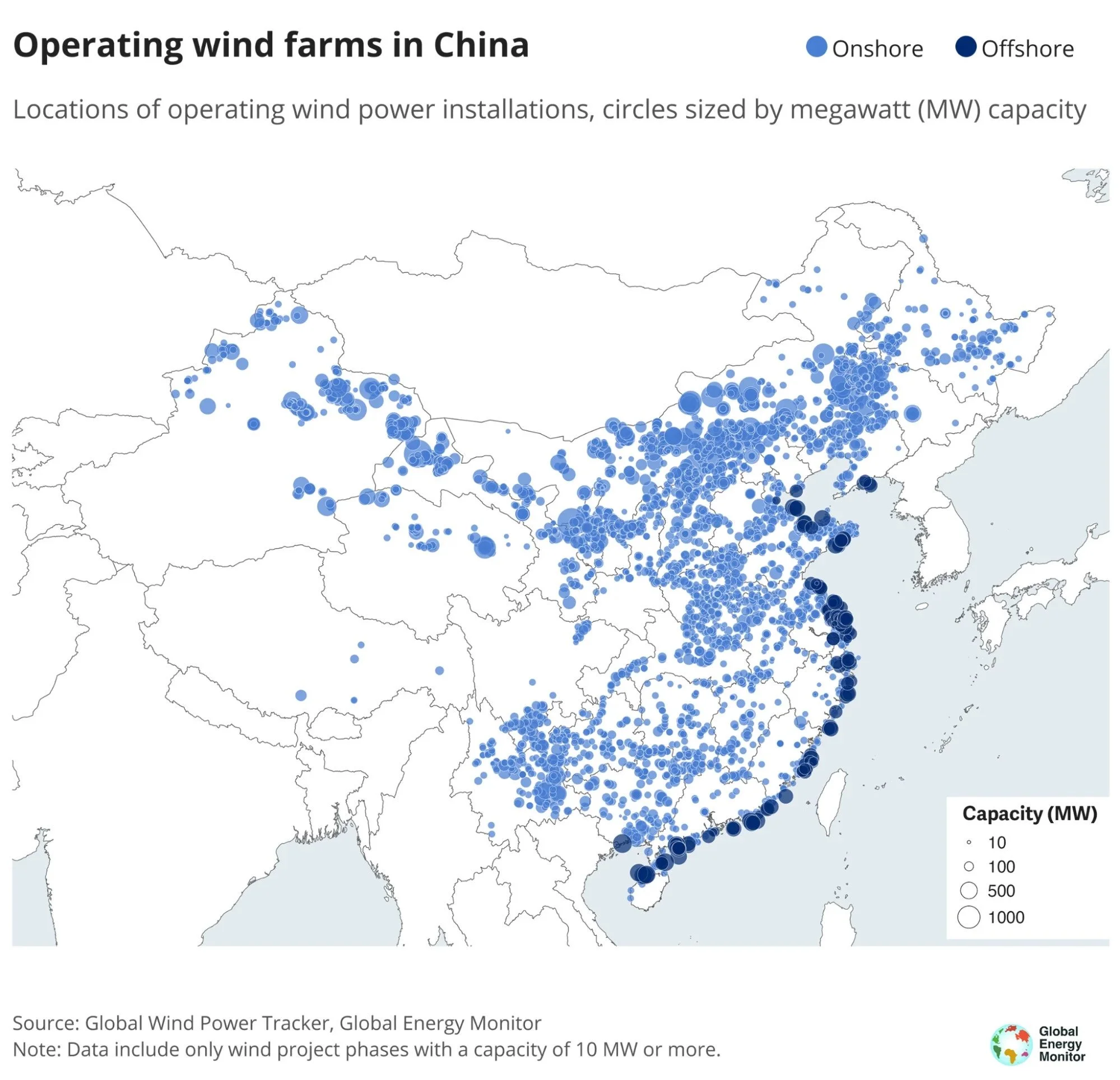

The country that will underpin this growth is of course China, as it doubles down hard on electrification and renewables as part of its “all of the above” energy security strategy. In 2025, China’s wind output grew 14%. But the scale of new capacity additions points to even faster growth ahead: it added an enormous 119 GW of new wind installations out of a new record global total of around 150 GW. That’s 50% more than in 2024 and equates to 17,000 individual turbines. And this doesn’t look like a one-off. Analysts at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), which tracks Chinese energy policy closely, sees the country entering a “new normal of over 100 GW per year growth”.

At around 10% of China’s power generation, there is plenty of scope for further Chinese wind expansion, especially in lesser populated western regions that are being connected to eastern megacities via new ultra-high voltage transmission lines. Meanwhile, the East and South China Seas collectively form the world’s largest offshore wind province.

Operating wind farms of >10MW in China. Source: Global Energy Monitor

The global scale-up still has much further to run

This plateau of productivity will be underpinned by Chinese and European competition to roll out larger turbines at greater scale. Unlike solar and batteries, wind remains one industry in which European companies can still see ways to compete.

Today’s gigascale offshore projects harness wind resources far more efficiently, thanks to turbines of up to 15MW or even 20MW, versus less than 2MW typically seen 25 years ago. Hornsea 1 was the UK North Sea’s first gigascale project at 1.2 GW. Now that is the average size for all new North Sea projects. When fully built, Dogger Bank A, B and C will claim to collectively form the world’s largest offshore wind farm at 3.6 GW. That is some serious scale, sufficient to power 6 million homes annually, or around a quarter of all UK homes.

While the focus in Europe has shifted towards standardising turbine sizes to enable supply chains to support efficient expansion, China’s relentless energy quest is testing new frontiers. China Three Gorges recently installed the first 20 MW turbine (manufactured by Goldwind) at the Zhangpu Liuao Phase 2 offshore wind farm. This 174 metre tall turbine, with a rotor diameter of 300 metres, is expected to generate over 80 GWh per year - the annual demand of 44,000 homes. Not to be outdone, Dongfang Electric is now testing a 26 MW model, while Ming Yang is even trying to develop a 50 MW twin-headed floating turbine…

Installation of Goldwind’s 20 MW turbine at China Three Gorges’ Zhangpu Liuao Phase 2. Source: Zhou Junwei / CTG

Chinese offshore projects are generally a similar size to new North Sea ones, in the 1-2 GW range, with the 1.7 GW Yangjiang Shaba being the largest to date. Onshore, however, China is shooting for another order of magnitude: the Gansu project in the northern Gobi desert is targeting a mind-boggling 20 GW on completion. That is more than the UK’s entire onshore capacity.

China will lead the way in absolute installation numbers for the foreseeable. However, growth rates across key demand regions including south and south-east Asia, Middle East, Africa and Latin America are already rising to meet considerable unfulfilled potential.

Implications for wind’s long-term global growth

Despite industry volatility, wind capacity actually grew at an impressive compound annual rate of 18% over 2020-25, adding up to a near-70% increase in global output. Strategic buildouts in China, Europe and a host of other emerging markets drive the next wave of growth. However, given progressively higher numbers, we assume capacity growth rate will fall to 8%/pa on average over the next five years. In that scenario, this takes annual installations beyond 200 GW/pa and lifts cumulative capacity over 2 TW by 2030, from 94 GW and 0.75 TW in 2020. Likewise, generation exceeds 4,000 TWh/pa from 1,600 TWh/pa in 2020. That represents 150% output growth over this decade alone. Wind would rise from 6% to 11% of total global electricity generation.

Historical data (2020-24; 2025 tbc): IEA, GWEC. Forecast 2026-30 data: Strome FOREST model.

Of 6 main electricity generation sources, wind is currently about level with solar and nuclear, but still well behind coal, gas and hydro. By 2040, solar will be comfortably the leading global power source, but wind (green line in chart below) will also overtake gas into second place, accounting for around 15% of global electricity generation. This assumes capacity growth moderates further to average 4.3%/pa over 2030-40. So there is scope for the outturn to be materially higher.

Global electricity generation by type, 2020-2040F. Historical data: IEA. Forecast data: Strome FOREST model.

A hybrid future

Another key factor supporting a consistent rollout of new wind capacity is the growth in stationary storage, as battery costs continue to fall. Battery co-location will help to maximise wind farm utilisation and underpin financial returns. Hybrid projects combining solar and/or wind with batteries are swiftly becoming the norm for new capacity. Or increasingly, integrating all three to produce the steadier, more dependable output that grids need. Likewise, key demand sources like data centres may be located closer to supply, to minimise grid constraints.

Risks

There are naturally several key risks to this outlook, to which wind developers and OEMs will remain exposed:

Macroeconomic: Interest rates appear to be well past their 2021-23 peak. But with sticky inflation, they may not fall much further either. Another inflation shock would push the cost of capital for large wind projects back up again.

Market: Electricity prices could fall to a point where new wind projects, particularly offshore ones, are not competitive enough to meet investment return hurdles. Although the real question is where wind’s all-in costs fall relative to other sources of new generation capacity for a given market.

Political: Governments could lose focus or fail to galvanise collective action. Russian gas returning meaningfully to Europe looks highly unlikely, but that could change. The US shows the risk of sharp reversals in government policy. The UK’s Reform party has threatened to cancel the CfD scheme, believing a US-style onshore shale gas revolution is the answer (despite no real evidence that it could work in the UK). However, reactionary voices are usually loudest in opposition and more pragmatic if they reach power. Indigenous energy endowments still need to be maximised, something which China and many other countries understand very well. The US’ abundant energy resources arguably allows it to indulge its leader’s energy blindness, but energy importing countries have a different calculus.

Regulatory: Establishing large-scale cross-border investment frameworks and CfDs in Europe will require negotiation and compromise, so positive outcomes are not guaranteed.

Technical: There are two risks here. First, either solar ends up being so efficient, cheap and quick to install that it effectively cannabalises wind’s future growth. Or second, that other technologies like advanced geothermal break through to outcompete new wind projects.

Systemic: Grid investment has lagged investment in generation capacity, creating severe connection backlogs. We expect this will rebalance as financial incentives evolve, but if not then wind’s scope for growth may be curtailed. That said, the battery storage revolution will help to alleviate grid congestion.

Getting exposed to wind

If this long-term growth thesis is more or less correct, what might be the best way to play it? Key listed players come in two main categories:

Big developers such as Ørsted, RWE, Iberdrola, China Longyuan, NextEra, Brookfield Renewable Partners and EDP Renovaveis - some being more “pure-play” wind while others are more diversified renewables utilities

Equipment manufacturers (OEMs) like Vestas, Nordex, GE, Ming Yang and Goldwind, leaders in a global wind supply chain that extends from all the component parts through to installation vessels

In simple terms, developers carry the risks and rewards of project delivery. To finance and build new projects, especially larger ones, they typically need government-backed long-term fixed-price arrangements like CfDs or power purchase agreements (PPAs) with large, creditworthy companies. OEMs compete to supply them while seeking to protect profit margins. Their business tends to be more cyclical in nature.

Chinese OEMs have come to dominate solar, battery and increasingly electric vehicle supply chains. Robust growth in their domestic market has enabled them to build unrivalled scale and cost efficiency. That in turn puts them in pole position to lead the rollout across emerging markets where most future demand growth will come. As China dominates wind capacity expansion, this may well happen in the wind sector, if in fact it hasn’t already. They also enjoy the backing of Chinese financial institutions to offer compelling commercial propositions. That said, Chinese OEMs also face their own fierce internal competition, as seen in solar and EVs.

European OEMs, meanwhile, are more focused on ensuring solid margins ahead of growth for growth’s sake. Instead of competing on cost, they seek differentiation as full-service providers, offering not just equipment but optimised systems, software and services for wind and hybrid wind-battery projects. No doubt AI will have a role to play here, in terms of predictive maintenance and maximising utilisation.

Comparative market performance

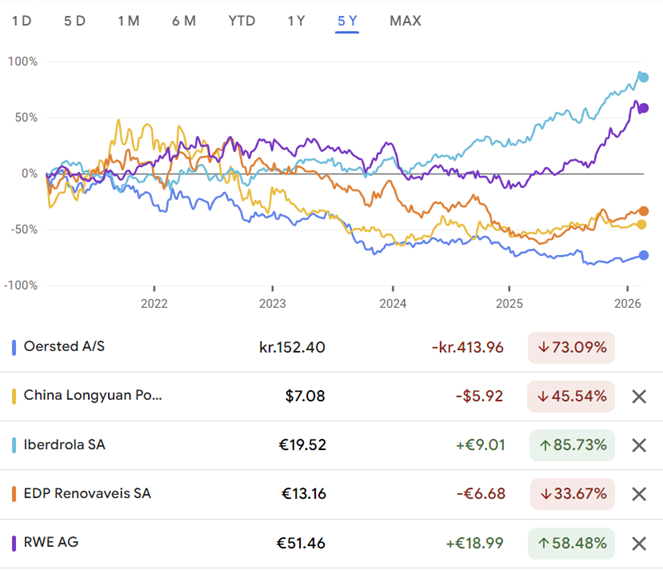

Major wind OEM share prices tell the story of the past 5 years: 2021-24 slump then recovery over 2025-26 to date. Perhaps we should have got around to this edition a year ago…

Simple share price comparison of selected wind OEMs: last 5 years, 19 Feb 2026

Nordex, the Hamburg-headquartered European OEM, has seen the strongest recovery, with its share price tripling over the year to early February 2026. Even with a slight pullback it currently trades at high price/earnings multiples (trailing P/E 74x, forward P/E 30x). Similarly, Vestas rose nearly 150% between April 2025 and early February 2026, but remains quite fully valued even after a sharp pullback this month (trailing P/E 27x, forward P/E 21x).

Simple share price comparison of selected wind OEMs: last 12 months, 19 Feb 2026

China’s Goldwind has rallied even harder, back to its $15-20/share range it last saw in 2021, from a low of just $4 in April 2025. With the share price doubling in just over 4 months since September 2025 before dipping since January. Its Hong Kong listing has a trailing P/E of 20 and a forward P/E of 11.

What about wind developers? Over the past year, big wind-focused utilities like Iberdrola, RWE and EDPR have all risen a lot too, albeit in steadier fashion. The outlier is Ørsted, which is not only a specialist wind developer, but now specifically a Europe-focused offshore wind specialist, after divesting its onshore business to Copenhagen Investment Partners.

Simple share price comparison of selected wind/renewable developers/utilities: 1 year view, 19 Feb 2026

Over a five year view, Ørsted has also lagged the broader renewable developer market by some distance, and remains nearly 75% down over that period.

Simple share price comparison of selected wind/renewable developers/utilities: last 5 years, 19 Feb 2026

Ørsted: a risky play on Europe’s doubling down on wind?

There are plenty of reasons to be cautious about Ørsted. Its share price performance reflects a litany of existential challenges over recent years as investors’ focus went from growth potential to execution risk, but is still not that cheap relative to projected earnings. Rising project costs and delays put its business model under severe pressure, forced a change of leadership, cancellation of its dividend and a deeply discounted fundraise to stay alive. Its foray into the US market put it on an arbitration collision course with the Trump administration and caught it in the crossfire of his Greenland ambitions. Ultimately, offshore wind is and always will be higher cost than onshore wind and of course solar. It remains vulnerable to inflation shocks. And it relies on the timely buildout of grid connections and interconnectors, creating project on project risks.

Despite all these valid risk factors, we still see potential further long-term upside for Ørsted. We cautiously added it to the Energized Portfolio in January, for the following reasons:

Specialist focus: Ørsted not only offers clear wind exposure, compared to other diversified renewables developers, but specifically offshore wind. Admittedly, that could be seen as a negative given the financing, development and cost risks. But in Europe at least it also offers a route to greater scale, higher capacity factors and higher realised prices underwritten by governments via CfDs or large creditworthy offtakers via PPAs. The strategic decision to narrow the focus to European offshore wind may well not have been entirely voluntary. But focusing on leadership in a core business is often a better strategy than trying to compete more broadly. It still leaves it with a substantial 8.1 GW development portfolio, including the 2.85 GW Hornsea 3 (UK), the 1.5 GW Baltica 2 (Poland) and 0.9 GW Borkum Riffgrund 3 (Germany).

European strategic industry: Equally, Ørsted likely has most to gain from the European vision of up to 15 GW/pa of new offshore projects out to 2040, supporting further growth of its long-term project pipeline. Ørsted has been semi-nationalised, with the Danish government now owning 50.1% and the Norwegian government also effectively a shareholder via the 10% strategic stake held by Equinor. That does not guarantee future valuation, but it does imply strong political support as it leads the growth of a strategic European industry.

Financial discipline: More scale only matters if it’s delivered profitably. Ørsted’s reset has seen a leadership change, a DKK 60bn rights issue and several major divestments. These painful steps have strengthened its balance sheet. A renewed focus on financial returns and disciplined capital allocation was demonstrated by the May 2025 decision to defer the 2.4 GW Hornsea 4. To be more competitive, Ørsted is also targeting a 30% reduction in the price of electricity from offshore wind by 2040. That implies a leaner operating model with more ambitious internal cost targets.

Recovery potential: As the turnaround progresses, Ørsted’s worst seems to be finally behind it. It returned to profitability in 2025 after two years of net losses. Its share price recovery has lagged its peers, but has been trending steadily upwards to around DKK 150 (forward P/E 23x) currently since the low of DKK 100 August 2025. We will need to take a long-term view, but patient buildout of a more resilient offshore portfolio can ultimately bring further recovery in value, cash flow and even the resumption of dividend payouts.

Wind ETFs

Rather than trying to pick one winner in wind, a less risky route to invest specifically in wind is via ETFs. These are also up 45-55% over the past 12 months, reflecting the widespread recovery across the sector. These have the benefit of some diversification, including across developers and OEMs across different geographies. There are three main ones available:

FIrst Trust Global Wind Energy ETF (FAN) - top 5 holdings: Vestas, Nordex, EDP Renovaveis, Englight, Orsted

Global X Wind Energy UCITS ETF (WNDG) - top 5 holdigs: Vestas, Orsted, China Three Gorges, EDP Renovaveis, Ming Yang Smart Energy

Invesco Wind ENergy UCITS ETF (WNDY) - top 5 holdings: Furukawa Electric, Enlight, Wasion, Energix, Daihen

Notes:

* A Contract for Difference (CfD) in renewables is a typically government-backed mechanism whereby a fixed-price or price formula is agreed for the ouptput of a given project. When the market price is below that reference price, the buyer compensates the seller for the difference, and vice versa when it is above it, so that the output is sold effectively at the reference price over time.

** A merchant project is exposed to the risk of actual market prices, rather than having a fixed price arrangement in place like a CfD or a PPA.

*** Over 2026, we are aiming to increase the Energized Portfolio from 10 to at least 20 long-term strategic investments (more detail on this in future editions). The focus is firmly on a buy-and-hold strategy, looking to identify energy investments with clear growth potential over at least a 5+ year outlook.